Esthi Zipori

Esthi remembers driving fast on the open road, friends sitting beside her, music blasting, yellow sand dunes stretching outward, and nothing but the headlights competing with the brilliance of the stars shining over the desert. It’s the ideal of driving sold to us in car commercials. But she’s driving an armored truck, and she and her friends have guns at their hips. They’re 19-year-old soldiers completing compulsory service in the Israeli military, guarding a base on the border zone between Israel, Egypt and Gaza.

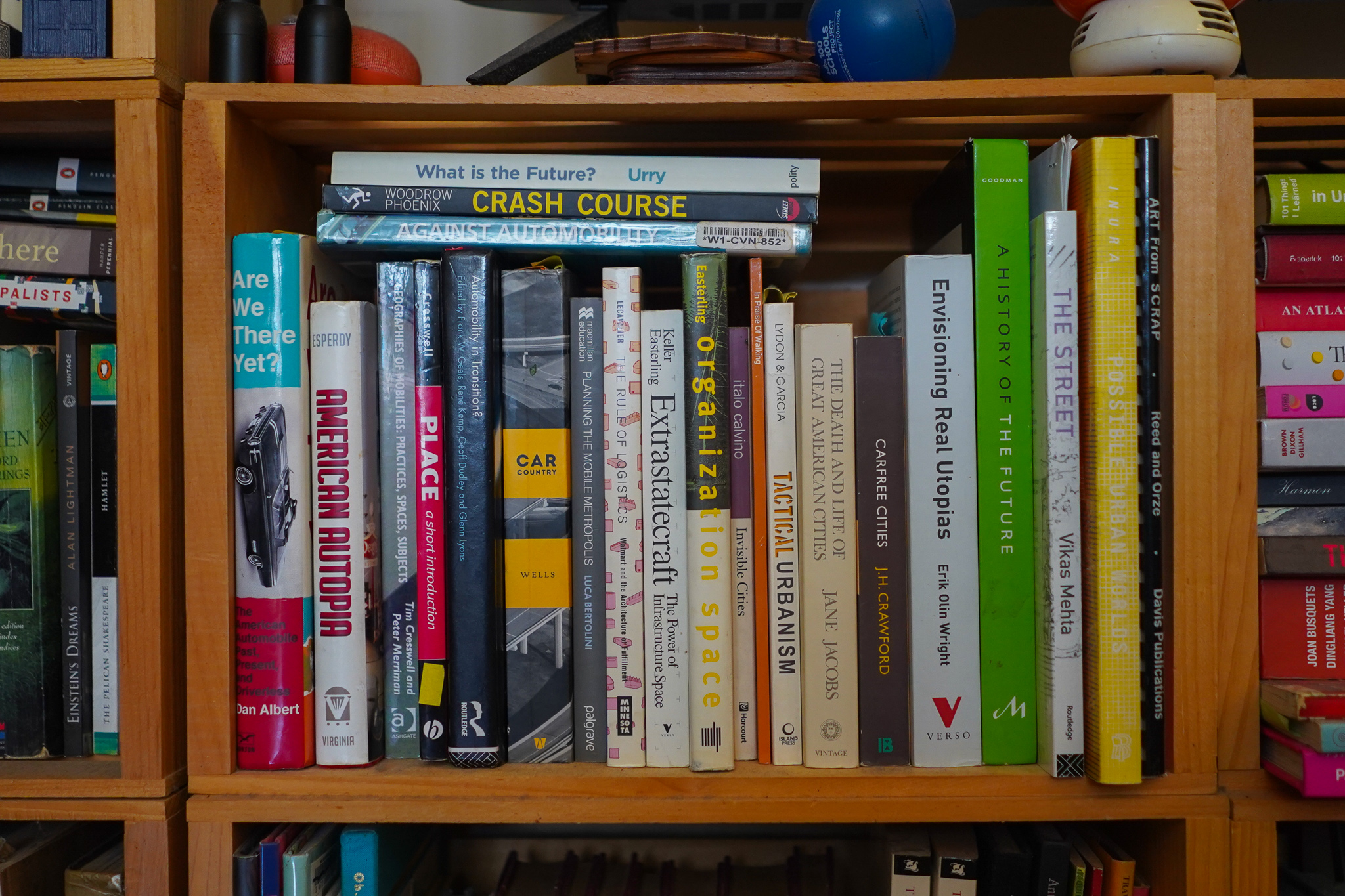

Esthi emerged from military service disillusioned. “I didn't want to live in a place where I have to constantly be at war with everything and everybody. I wanted to be in a place where I can just be me, and work toward something, do something meaningful,” she reflected. She decided to study abroad, and is still studying today. As a doctoral student at New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT), she researches urban streets, sustainable mobility, and the realities of using cars. “I'm focused on this question about the future of streets, and a big part of the future of streets has to do with the present, which is cars,” Esthi said. Studying urban form, she learned about the numbers of fatalities and injuries caused by the car system, and came to see automobiles as a menace.

Listen to Esthi reflect on her relationship with cars:

Click to Read Transcript

Now I'm working on my PhD in urban systems. So, I've studied the car system now for almost six years, and it is terrifying. The roadway is a scary, scary place. I mean, when you look at the numbers of fatalities and injuries of people inside cars, people outside of cars, it's just like a menace. And now I just see it all the time, everywhere I go.

But the government, the policies, the obsession with cars, you know, people just want to be comfortable. So, I did a lot of driving in my life, too. And now as someone who identifies as a car-free human, I find it very amusing, cause I do love fast cars and I would love to go on a track and drive really fast, but I really despise them in cities [laughs].

Now, even if I moved to a place that might require a car, I'm gonna make sure that I figure out a way to live without it.

Through her studies, she was taken with the idea of post-automobility, a future where people don’t rely on automobiles. She sold her car in 2015, and has relied on public transportation, walking, and biking ever since. “With the climate emergency, I'm one of the very anxious persons. I worry about the future of all of us,” she said. “I don't think we're doing enough and I don't think we're doing it quick enough.”

She sees programs like Open Streets as a solution that can mitigate harm to the environment. Esthi and her husband, Mark Blinder, were delighted when 34th Avenue closed to cars. “We loved it from the moment we saw it. Because of my research and my advocacy that stems from that research, we're big fans.”

Esthi experiences the 34th Avenue Open Street as an academic and as a vendor – she and Mark make up the Sandwich Therapy duo, selling Israeli/Georgian/Middle Eastern sandwiches, salads, bowls, and desserts on 34th Avenue.

Mark was between jobs when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and during the ensuing hiring freeze his H-1B visa, which had allowed him to practice his profession as a social worker, expired. He began cooking more and toyed with the idea of selling food. When 34th Avenue became an Open Street, he finally decided to give it a shot. They live around the corner from Travers Park, the only park in Jackson Heights, which borders on 34th Avenue. One day in September 2020, Mark made some shakshuka and fried eggplant sandwiches, put them in a thermal bag, and headed to the park. He didn’t sell much.

Mark and Esthi quickly realized they needed a proper vending station, and acquired a folding table and the necessary materials. They moved from the park to the avenue, and established a regular schedule on weekends. Sandwich Therapy was born. Within a month and a half, it became their main source of income; they usually make $300-500 a weekend, as long as the weather isn’t too bad.

On a warm Saturday in September 2021, the sprinkler in Travers Park was on, kids screeched as they splashed in the water, and people peeled off layers of clothing to sunbathe on the park’s sole patch of grass. Esthi, with blue hair and blue-tinted shades, appeared on the Open Street pulling a blue wagon full of food to her usual spot: a patch of cement on the median hemmed in by shrubbery and sunflowers. “Medians fall between the cracks of urban management,” Esthi said. They aren’t governed by the rules that apply to sidewalks, crosswalks, and parks, and are friendlier spots for vendors.

She set up their blue canopy tent, covered their folding table with a blue tablecloth, and hung up signs with reusable velcro advertising the menu for the day. On the table she arranged food samples with toothpicks and labels, and her original artwork.

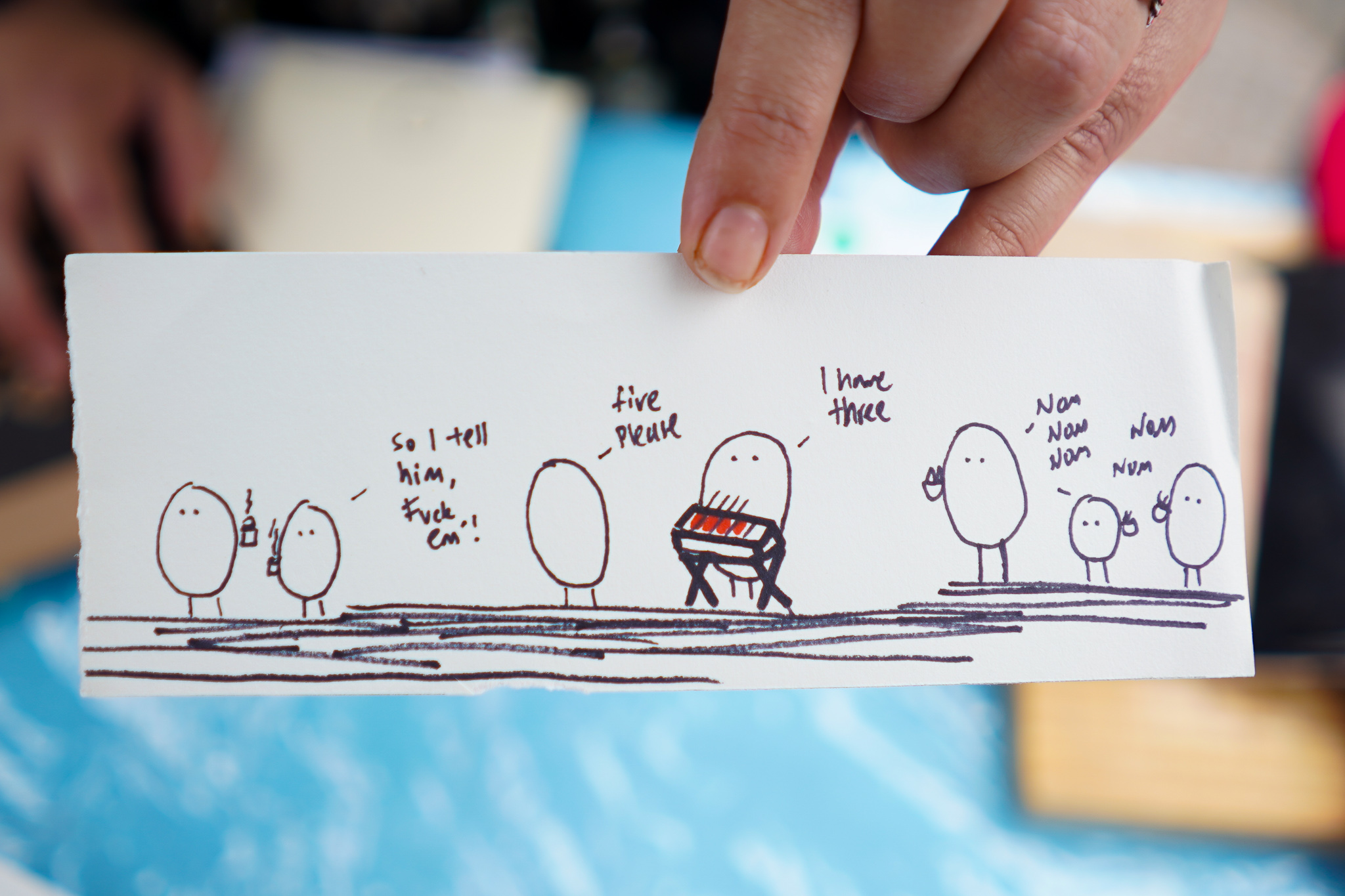

Before studying architecture and urban systems, Esthi went to art school. She keeps up an artistic practice, painting abstract pieces that play with color and texture and drawing whimsical cartoons she calls “Egg Buddies.” Some drawings are inspired by her vending experiences: the egg characters stand on the street drinking tea and chatting. She frames and sells some pieces at the Sandwich Therapy stand. “It’s more of an outdoor art exhibit than a serious attempt to sell,” she’s quick to explain.

She was hoping to grade some of her students’ assignments while vending, but realized she’d forgotten to bring her notebook with grades. She’d wait an hour until Mark dropped by. While Esthi operates their stand, Mark cooks at home and visits the station to replenish their offerings and give Esthi bathroom breaks.

While many other vendors in the area sell at high volume and low price points, Sandwich Therapy offers pricier, but more substantial meals, like hearty chicken schnitzel sandwiches; chakhokhbili, a Georgian chicken stew; and shakshuka bowls with tomatoes, pepper, onion, and eggs over rice. “We love the food we make,” Esthi said. “We eat all the leftovers.”

A regular customer, Richard Osterweil, stopped by. He didn’t have to tell Esthi what he wanted; he always gets borscht. “This soup is wonderful!” Richard rhapsodized. “It gets me through the week. And it helps me lose weight because it’s very filling and low calorie.” Mark was making summer borscht, a kefir-based cold beet soup with potato, onion, cucumber, radish, and boiled egg, but next week planned to switch to winter borscht, a hot version with cabbage.

Richard asked Esthi about what she was reading. In the middle of their conversation, a plastic bag blew by. “Hold on!” Esthi yelped. She chased down the bag, then placed it in the small garbage bag at her station.

Esthi vends on Saturdays and Sundays from 11am till 3pm, closing earlier when they sell out. In between customers, she reads, listens to music, and tries to do work, but mostly she sits and observes. Spending several hours on 34th Avenue each week, she’s gained an intimate familiarity with the street’s rhythms. Below, Esthi describes what she sees and hears on the Open Street:

Click to Read Transcript

One of the biggest things I notice always is the breeze, how lovely the breeze is on the Open Street. And how quiet. I just love that you can't hear cars. I love that you hear snips of music. Like a week ago, there was a guy with a violin playing on 34th and 78th. And it was just the best.

In terms of older people, you see more of them walking safely in the road, meeting some friends. Right on 34th and 77th, there's the park, and they put a bunch of benches right next to the curb. Before that [creation of the Open Street], you didn't have anything to watch. Like, you'd watch the car drive. But now, you have people watching and you can see them gossiping about everything and everybody.

And with the kids is the ability to run. I see a bunch of 14 year olds riding bikes by themselves, no parents’ supervision required. You can see a kid–even the younger kids, five, six–and they're running around and they're saying hi to other kids in the streets. I think that's my favorite thing, seeing small kids biking or scooting by themselves and seeing the parents not running after them like crazy, like they have to do in the sidewalks, but just crawling behind. I see so many kids making noise [laughs] and that's what the streets are for, to get all their energy out and run around and bike.

And it's just so nice to hear those sounds when I'm out there in the street, than honking and revving and just the constant white noise of cars driving. Yeah. The quiet, though, the quiet. You notice when the Open Streets ends and, even from my apartment, you start hearing the honks a lot more.

I really enjoy sometimes randomly seeing the people doing Zumba, or seeing another street vendor. I love street vendors of all kinds, especially when they're selling something that I haven't seen before being sold on the street. Some people sometimes leave books, which I also love. I love those kind of, you know, leaving a few things with the note, "Take me, I'm free.”

Oh, I know! And the butterflies! I've noticed I keep seeing huge butterflies, gorgeous--I recently saw one orange with, like, a black pattern. Just absolutely gorgeous. And I love squirrel-watching. Even though I've been here for more than a decade, squirrels get me excited every time I see them. It's just like, I can't believe this is the normal animal running around in our city. It's just so awesome.

She also sees elements of her studies play out in the theater of the street, sometimes witnessing clashes between pedestrians and drivers. The “us vs. them” mentality held by some pedestrians and drivers reminds her of why she wanted to leave Israel.

Here Esthi explains how the Open Street feels like a battlefield:

Click to Read Transcript

So, when I'm on the Open Street, I get to see those policies live. I get to see sometimes the small fights between the drivers that are so pissed that they had to get out of their car to move the barricade, so they don't move the barricade back, and they make sure that they drive really fast through the street to take their turn, right? Or the pedestrians that, even though a car driver tries to be, you know, somewhat respectable will kind of hit them--the cars, I mean--and will be like, "No, you're not supposed to be here." Or sometimes where a pedestrian will help car drivers and be like, "Yeah, I'll close the gate for you. Don't worry about it." I see more often the incidents of drivers being frustrated by the Open Street than pedestrians yelling at car drivers.

I think the Open Street, it breaks the mold. And that’s what’s so scary for so many people. They don't know how to deal with it. And for some of them, the street is a battlefield.

I told Mark the other day, for me, I grew up at a time period where buses exploded. So, I really got desensitized about all of that. And that's what happens in Israel really. Cause it happens all the time. And you have to find someone to blame, right? I think living outside of Israel really gave me a lot of perspective on a lot of things, and also being in the United States so long that I've also kind of seen behind the screen of what America tells everybody it is and what it actually is, that I now also understand the curtain that we put on ourselves in Israel, and what we tell ourselves that we are, and then how we actually behave.

But yeah, also, you know, the American car culture has totally taken over Israel. And it's such a tiny country that it's really, really difficult, like, you can't go anywhere without a car. And you're pretty much in traffic all the time because everybody's in their own car. So not only are they constantly stressed about getting shot at or stabbed and all the trauma of each person's own military experience, and then all the stress from being in cars; it's just kind of a pocket of pressure all the time.

I mean, violence is complicated, especially when you're fighting for something you believe is your freedom. Who can tell you that it's not? And then why is that not allowed? Right? Like we see it in movies all the time, but if it's a white American dude, it's freedom. But when it's an Arab, suddenly it's not. Now those are conversations I wish I could have with my brother, for example, but he's so locked into the mindset of us versus them.

And I know it's weird to say that it's the same with people driving cars and pedestrians, but that's how they frame it a lot of times, right? Us versus them. “You're trying to take something away from us that's ours.” And if we can't have conversations about cars amongst the same communities, how can we expect to have conversations on much more complicated stuff between countries?

In this battleground, people are warring over potential futures, and Esthi is firmly entrenched, fighting through education.

“I always felt like maybe I can contribute a bit more into making life better,” Esthi said. She’s found her calling in contributing to our understanding of urban systems. She teaches at NJIT and encourages her students to imagine what’s possible for the future. In a class she created, “From Private Cars to Public Spaces: An Exploration of the Green New Deal,” she asked students to design 15-minute cities, neighborhoods where daily necessities can be accomplished without cars.

Esthi also teaches about the past and future of streets. Listen below for her rundown on the history of streets:

Click to Read Transcript

Bridget: Can you tell me about the history of streets?

Esthi: Oh yeah, of course, I would love to tell you about the history of streets. In terms of the United States, I think, and New York City in particular, by the 1900s, you have streets, what we understand as modern streets. We have sidewalks; that's been around for several decades. But most of the streets are dirt paths, muddy, there's no main body that cleans it or maintains it. The responsibility is purely on the people who live on those blocks. And the main uses in the streets is horse carriages. And then there's the first invented bus in like the early 1920s, the Omnibus, which is the first kind of public transit vehicle that actually you can pick up anywhere and it drops you anywhere. It's like limited to 12, 15 people. You start seeing electrical cars, actually, before you see the gasoline cars. You see the bicycle getting used.

The bicycle and the electrical car were really huge liberators for women to be able to independently travel. And that's also actually one of the reasons why both of those tools were pushed to the side fairly hard on, to prevent that kind of independence. The bicycle actually started as like a rich people toy, and only after some technological innovation that made the wheel wider and the gears easier to use, then women start using them more seriously for independent travel. And actually bicycle riders are the organization that pushes paving of streets, because all of the mud and the horses' mess, and it's really bad for the bikes and they keep falling off.

So, when we started getting these innovations in pavings in the 1920s, and then we start to get innovation in combustion engine, private vehicles. And even though they explode, and even though they're pretty difficult to maneuver, they're fast and they begin to be associated with power and freedom and independence. So you know, all the white males jump on the opportunity. And we see this rise in middle class that takes over governmental positions and legislates laws that start to organize the streets, start to kind of introduce traffic lights and stoplights, and this idea of a crosswalk, that you're supposed to cross in corners.

And there's huge fights against this. Thousands of kids die in the streets; mostly kids because they're used to playing in the streets because the streets was the public spaces. There weren't parks or playgrounds or any of that sort. That's kinda only still getting developed. So there's this really big push, especially from women, against this kind of increase in combustion engine cars, but the lobby of car manufacturing and all of the supporting industry around it, they win the game, right? Investing in a lot of marketing, inventing jaywalking, doing this whole kind of psychological thing over the years where it's your fault for being run over. You should be more responsible and make your way for the fast-moving car.

And then you probably know the rest of the story with Ford, right? Henry Ford comes in and brings together a collection of technology, but most importantly, the assembly line. He makes car production way more efficient, way more quicker, more affordable. He gives his employees a raise, so they can actually buy the T models that they're producing. And he also gives them days off, because he wants them to buy his cars, and then he wants them to use them and make other people want to buy the car. So Henry Ford really creates this new form of production that spreads everywhere. In that time period, like 1930s, 1940s, the roads are still a mess, like they're paved, but there's no marking, there's not too many traffic signs. The concept of parking and parking meters is getting invented because they're starting to see demand of space.

But then comes World War II. And World War II changes everything, because when the war ends and everybody comes back, there's the push to put women back in the house. And there's a need to sell a lot of things, right, to maintain the consumer society. And one of those things is the car. And the car becomes the tool to keep separating everything. That's when we start seeing cities really separating residential from commercial, from business and industry. Instead, cities are a mix of all, right? But cities are getting vilified by investing in suburbs instead. Really creating the suburbs, that people need cars to drive back to the city to work.

And through the fifties all the way until the 1990s, you see policies continuously privilege the car. From the development of, in the 1960s, we have the national interstate system that cuts through cities and communities, mostly African-American, mostly Brown communities, cutting them in half, completely displacing them, and putting huge intersections and huge urban highways in almost every single American city. And it's just like someone just came in with a knife and put a highway there, a highway there, and there's some leftovers from the community, but you could still see the brokenness of it.

So we have Robert Moses coming in, that's these time periods as well, in the 60s, 70s. On the one hand, without him, all the kind of commercial connections that make New York City what it is today, on the other hand, he was a firm believer of what's called the automobile lifestyle. One of the first parkways that he built to the beach have, on purpose, really low bridges, right? That's the most known fact about them, that the buses can’t go underneath them. And by the 1980s, American urban streets are roadways. Period.

So, the last hundred years, not too much changed. Not too much changed in car technology, not too much has changed in road technology. Cars have become extremely safer for people inside, and extremely, extremely dangerous for people outside. Especially in terms of size, the cars are getting bigger and bigger.

The street is public space, but we've looked at it in the last 50 years as a throughway, not an urban place. And that's the difference. That's kind of the big transition that is there; that it used to be an urban place that serviced that community, both traveling through it and living in it. Now it doesn't. Yeah, streets are fascinating.

Bridget: Thank you for that super comprehensive and informative overview–

Esthi: [Laughs] Can you tell I teach?

Bridget: Yeah, that was really great. I feel like I just learned so much. Just seeing the bigger picture all at once through that explanation, and it's pretty depressing.

Esthi Zipori: It can be. I know. That's why it's so important to remember the points of lights, like the Open Streets ideas and the Summer Streets, and do what we can to push it forward. Because, that’s my argument, if the street was something else, why can’t we change it?

Esthi shows optimism for her students as she encourages them to dream up better worlds. “I have to open their minds to what can we do. And to do that, I have to be kind of almost like a Disney princess a little bit, that says, ‘Yes, we can do it!’”

Yet she is gripped by anxiety over the climate crisis and the future of our planet. In her dissertation, she argues that we’re already living in a dystopia. She doesn't plan to have children. “I just can't mentally deal with having a baby and then when they grow up telling them, ‘Welcome to planet earth. Everything's on fire. I knew everything was on fire and I still brought you here.’”

She thought the pandemic could be an opportunity for real change. “In social science, crisis is an opportunity,” she said. ”I always thought, all we need is a crisis as a society. It will get our shit together and we will be able to face the climate crisis. We can better our society, readjust our values and all that jazz. And then we didn't.“ The infrastructural failure of society frustrates her.

In many ways, she’s feeling increasingly pessimistic, but programs like Open Streets present a ray of hope. She believes that by shifting away from personal car usage, making urban streets easier to walk and bike, we can transition our built environments towards a sustainable society.

Esthi has loved Jackson Heights since she moved there: “We feel more at home here than any other neighborhood, because there are so many people like us,” she said. “So many immigrants, so many people missing their families, but loving it here.” Below, Esthi explains what makes her neighborhood special:

Click to Read Transcript

That's what was always awesome about Jackson Heights, that we felt so much more at home here than any other neighborhood we lived at, because there was so many other people like us, and they were all at home and they're all like, "Yeah, this is our home. It's fine, it's okay that you speak another language and that you love all these other foods, and that you're not American. You're from Jackson Heights!” So I think that's been really meaningful.

And I know the waitress at Ricky's [Cafe]. The cashiers in the supermarket know me and will say hello. We have a bunch of our favorite restaurants that, even though I'm very white and I can blend very much in, but they'll still accept us, you know, even if it's a Bangladeshi spot or a Lebanese food place. And yeah, we're all just in Jackson Heights. And I don't think I've had that feeling, that kind of relationship with people and that kind of feeling of acceptance.

I mean, there are so many immigrants and so many people coming in here just looking for something different, looking for something else. Missing their families, but still loving it here. You know, having those multiple languages and loving all these different foods that they never heard about before. And also having that same anxiety, that same fear, and that same, "Oh, I wish I could vote, but I can't." Still being involved in all the politics and the community, but kind of also having that distance and kind of knowing that you can find cash jobs in the neighborhood, you could do street vending, and will be supported by the community. And that there’s resources.

And the food, I got to say, the food really made us feel at home here, because we could finally find fruits and vegetables and the things that we like to eat that before that was always such a struggle to find.

And then with the Open Streets, we got to meet our neighbors a lot more, and our community a lot more, and get involved with all sorts of stuff. So I think it really connected us to the neighborhood so much more than we were before. Yeah, you'll have to drag us kicking and screaming [laughs] out of the neighborhood.

Since 34th Avenue became an Open Street, she’s come to love Jackson Heights even more. “The Open Street just kind of made it even more part of our lives and part of who we are,” Esthi explained. “It connected us to the neighborhood so much more. Being on the Open Street and seeing the fun and good things it gives people, it’s done wonders for my mental well-being.”

Esthi is on a student visa and will soon be graduating. Because of her legal status, the future is uncertain, but she hopes to stay in Jackson Heights and see how the Open Street evolves. “There's like a clock always off to the sides, kind of ticking away, that puts in question our place here, because of our status as immigrants,” she said. “I really, really hope I succeed in staying here long enough to see it become what it could be.”

She hopes to see improvements, like removal of parking lanes in Open Streets, expanded bike lanes, permanent infrastructure, and community input on design and amenities. She hopes the community will push further and pedestrianize more streets.

“34th Avenue is proof of how much urban space influences our individual and personal lives, and how we can bring joy and happiness with only minor changes,” Esthi said. “Can you imagine how amazing it would be if we didn’t just settle for the minor changes?”

Published June 2022