Erick Modesto

"The dance studio has been the place where I could relieve my stress," said Erick Modesto, the director of traditional Mexican dance group Ballet Folklorico Nueva Juventud. "I would dance it off, sweat it off."

But in March 2020, the Covid-19 outbreak closed studios and theaters in New York City. Ballet Folklorico Nueva Juventud's dance performances were canceled. Erick couldn't even assemble his troupe in a studio to practice.

But he didn't stop dancing. He started holding rehearsals on 34th Avenue.

"I kept saying, how can we adapt to this? We don't want to just quit and wait until everything is over. We want to be able to still create work and find new ways to engage an audience," said Erick. "I wasn't going to let any more time go by and let my experience and training go down the drain."

A Jackson Heights native, Erick knew that some parts of the neighborhood that used to be unsafe, like Travers Park, are now more welcoming.

He initially considered rehearsing in Travers, one of the few parks in the area. But he scoped it out and saw people were already holding Zumba, tai chi and flamenco classes there. “There were so many activities going on, there was no room for any other activity,” he said. “I was disappointed because we lacked space to rehearse, but I love that people didn’t let the pandemic stop them. I was smiling under my mask throughout the whole entire park.”

The pandemic didn't stop Erick, either.

Here, Erick describes his experience on 34th Avenue:

Click to Read Transcript

Using 34th Avenue is very new for me. And it was really fun. I really felt super ecstatic. It almost felt like my first time being on stage, you know, without the lights, without the curtains.

But just the sense of performing, and just the sense of showing the public that this is what I do. And this is what I love. This is what I live for. This is what financially stabilized me before the pandemic.

And so, seeing the different diversity that was there, it wowed me. I would have never imagined that, in my years of living in Jackson Heights, that I would've seen the community come together more than ever.

This is the perfect example that we all share the same space, no matter where we come from, we're all here. And whether we like it or not, we're here to stay [laughs].

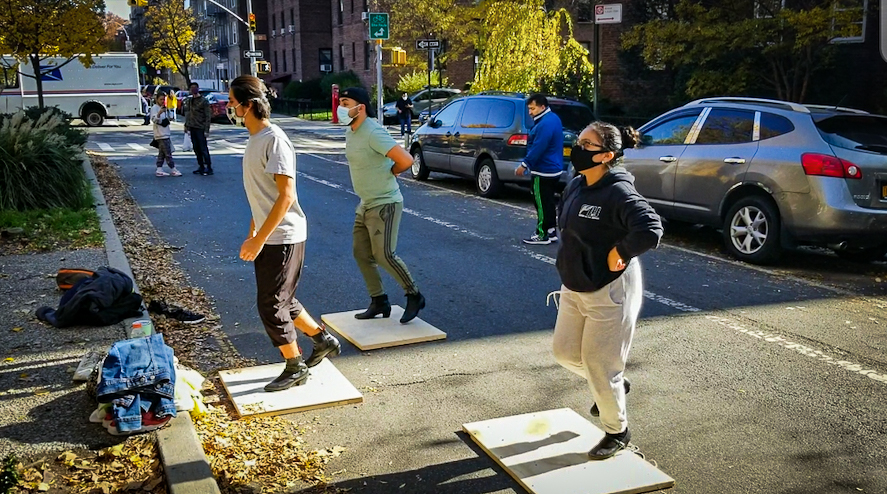

On a bright Sunday morning in early November 2020, Erick met up with two group members on 34th Avenue between 81st and 82nd Street. They sat on the median and changed from sneakers to botas, folklorico dancing shoes with nails hammered into the bottom. Erick laid down wooden platforms that his father, a carpenter, made for their rehearsals. The wooden boards amplify the percussive sound of their footwork, and provide a buffer against the concrete, which can be hard on dancers’ bodies and wear down their shoes.

Erick and the dancers each stood on an individual platform, 25 by 28 inches wide, and started reviewing some steps. Standing in front, Erick demonstrated footwork, hand motions, spins, and kicks, with precise movements. “One, two, three, four, five, six, and step out,” he called. “On the sixth one, instead of bringing your leg out, mark it as a stomp and a small pause.” Soon arms were sweeping and feet were stomping rhythmically.

A woman walking a dog stopped, asked what kind of dance they were doing, and remarked, “It’s wonderful to have you here.”

Moments later a man in a three-piece suit, Matt Moran, approached. “Good morning,” he said. “I love what you do. We have one conflict though.” Matt was from Saint Mark’s Episcopal Church, on the next block, diagonally across from where Erick and the dancers were rehearsing. The church had been closed since their pastor died of coronavirus in April 2020, but recently started holding services again in their garden. They were about to start a service. “The stomping is a little loud,” Matt explained with a wince, as if lodging the complaint pained him.

Erick apologized and stepped off his wooden platform. Matt added sheepishly, “I heard you yesterday and said, ‘This is joy in life.'"

With a good natured smile, Erick promised to keep the noise down until the service ended. The dancers set aside their platforms and continued rehearsing on the cement of the avenue.

“We have to respect everyone else’s activities,” Erick said. “We always have to adapt.”

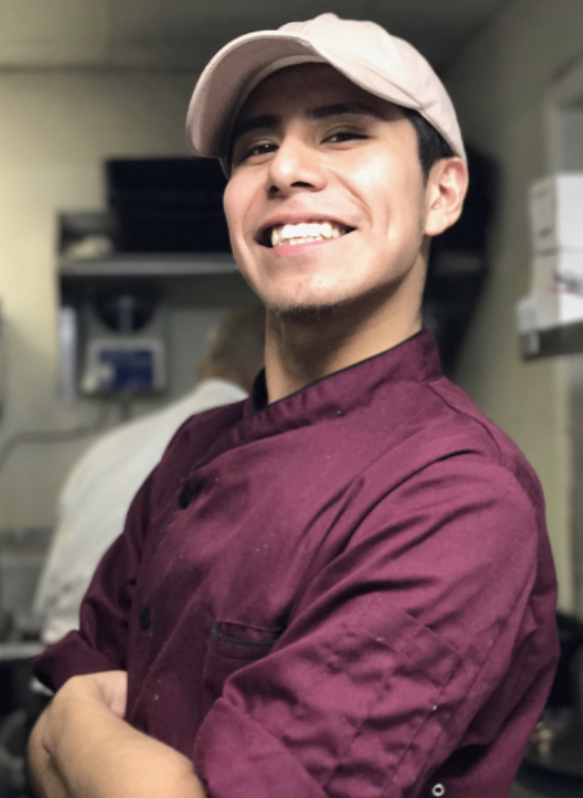

The winter cold finally did bring the outdoor rehearsals to an end. Ballet Folklorico Nueva Juventud took a winter break, and Erick concentrated on other work. Like most dancers, he relies on multiple jobs to sustain himself financially. He also dances with another company, Ballet Nepantla, but his main source of income came from working as a pastry chef. He would work long hours in the kitchen, and go straight to rehearsal with Ballet Nepantla on weekends and Ballet Folklorico Nueva Juventud on weekdays.

Before the pandemic, he was working full time at The Clocktower, a Michelin-starred restaurant in Manhattan. When non-essential businesses closed in March 2020, his sources of income as a dancer and chef were suddenly gone. "That gave me anxiety, worrying, how am I going to make it through? How long is this gonna continue?"

Naturally, while quarantining with his family in Jackson Heights, Erick, who is vegan, baked treats for them. His sister, Erika, encouraged him to try selling his pastries. Since 2020, the combination of restaurant closures and unemployment has led to a rise in home-based kitchens. Erick started an Instagram account and joined the ranks of new entrepreneurs selling homemade food out of their private kitchens. Now, in the incredibly diverse Jackson Heights dining scene, Erick's baking business, Veganity, fills a void for vegan sweets.

Erika was not only Erick's taste tester, but also his first customer and hype man. The siblings got the word out to friends and co-workers, and promoted Veganity on social media. The income this brought in helped Erick through the pandemic. Now he has loyal customers.

Ballet Folklorico Nueva Juventud resumed outdoor rehearsals in May of 2021.

On a hot, humid Saturday morning in late May, Erick and three dancers gathered at their usual spot on 34th Avenue.

This day the three dancers were all women, each wearing short-sleeved t-shirts and colorful traditional skirts with leggings underneath, and Mary Jane-style bota shoes with short socks. Everyone wore masks.

They reviewed choreography and sequences, concentrating on foot work and skirt work. The women gathered their skirts in both hands and opened their arms, creating beautiful swirling movements. In the bike lane behind them, bikers zoomed by.

“That arm should be down rather than up,” Erick directed. “On that double, take all six counts. Skirts all the way up. One, two, three, angle yourself. Four, five, six.”

At first they tapped out the beat with their feet. Then, Erick put on music. The uptempo mariachi music of Las Alazanas, a popular song from the state of Jalisco, floated from the speakers. A woman passing by called out, “I love it! It’s so good!”

Some joggers jogged around them; other passersby slowed down to look at the dancers; some stopped to take pictures or videos. A man on a motorcycle popped his kickstand and settled in to watch. A woman pushing a stroller with a sleeping baby stopped, put her foot up on the median, rested a hand on her hip, and enjoyed the show. After several songs, she applauded and kept walking down the Open Street.

Erick has become adept at negotiating the shared space of 34th Avenue. Throughout the rehearsal, he graciously accepted the occasional compliments from passersby, and smoothly handled the sporadic interruptions. When a car pulled out of a spot behind them, the dancers paused and made space for it to pass. The driver called out, “Thank you!” “You’re welcome!” Erick replied as he pulled away.

Empty parking spaces don't last long in Jackson Heights. Moments later, a driver moved the barricade aside and nabbed the vacated spot.

The dancers made it all look effortless, but the temperature had climbed to 90 degrees. The only evidence of exertion showed when one dancer removed her mask to wipe her red, sweaty face.

“You get used to it,” said Cindy, one of the dancers, who has been practicing ballet folklorico since she was seven years old.

Erick has also been practicing since he was seven, when his mother enrolled him and his sisters in Ballet Folklorico Nueva Juventud. Three brothers, Damaso, Edolay, and Jose Vargas - who happened to live right across the street from Erick's family - created the group to educate local youth in Mexican traditions. They met after school at St. Joan of Arc church on 35th Avenue.

After more than a decade, the brothers decided to focus on their families and stop leading the dance group. They asked the dancers if anyone wanted to take over Ballet Folklorico Nueva Juventud. "I was 18 at the time, a full-time college student with a full-time job," said Erick, who is now 26. After some hesitation, he stepped up to take on the role of director.

It was a bumpy transition from group member to director; most of the other dancers ended up leaving the group. "I bit off more than I could chew," Erick remembers. But he gained experience, learned to become a better teacher, and eventually fell into a rhythm.

Today he is proud to be continuing the work of the Vargas brothers, educating the next generation, and showing that traditions will continue no matter where you are.

Published July 2021